Life At Central

When Horace Greeley penned the famous words ‘Go West Young Man” in 1865, he was encouraging people to leave the comfort of life on America’s east coast and come to the wilderness frontier. (It now appears John B. L. Soule first wrote the words in an 1851 Terre Haute Express editorial.) Greeley knew about the frontier personally, not just from writing. He had been a stockholder and Agent for the Delaware Mine, a copper mine just north of the Central mine.

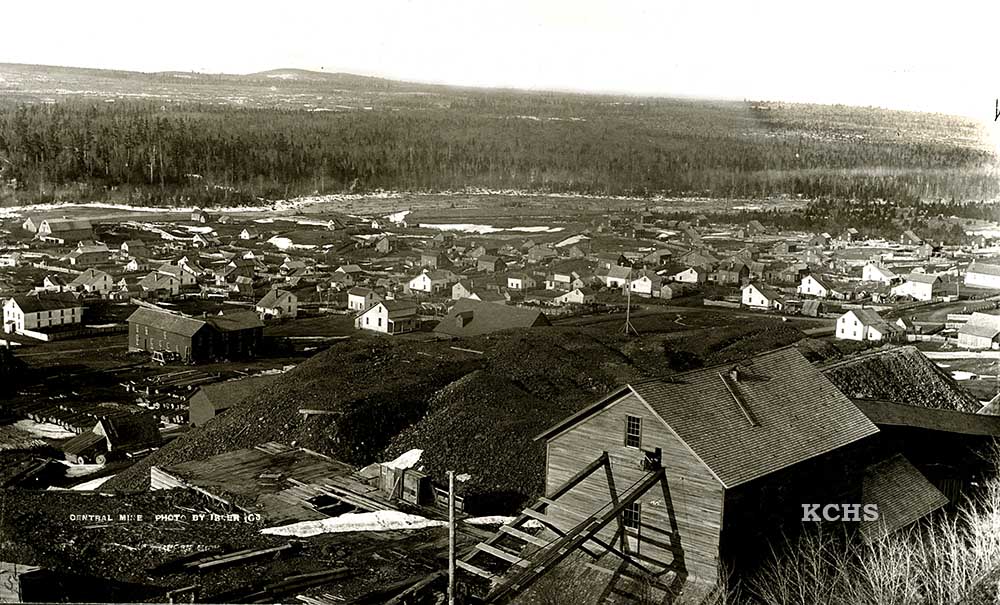

This

1896 photo was shot from the mine site overlooking the town. Central

later had a population of over 1,200 and 130 homes. (KCHS)

This

1896 photo was shot from the mine site overlooking the town. Central

later had a population of over 1,200 and 130 homes. (KCHS)

Greeley spent time in the Michigan frontier during the summers of 1847 and 1848. He was part of America’s first mineral rush, a rush that preceded the California gold rush. As Greeley and others predicted, many did come west to Michigan and other states to seek their fortunes. As they came, they brought their traditions and customs with them. While Michigan copper mine communities had individuals from many areas, the town of Central had a large number of workers from Cornwall in the British Isles. There were so many of these “Cousin Jacks” working at Central it’s said that any native-born American who visited the Central soon wished that they had brought an interpreter to decode the Cornish language spoken so freely at Central. (See the Keweenaw Kernewek web site for more information about the Cornish at Central.)

What was life like in this largely Cornish mining community? Alfred Nicholls was a miner at Central until he was injured in an accident. He then went to college, and returned to become a teacher and later principal of the Central school. He later wrote two books describing life in the early mining community. He described the town as

“The business enterprise of the vicinity consisted of a general store, also a meat market. A lone quaint little church seemed adequate accommodation for all purposes religiously; a schoolhouse met their needs intellectually. The social activities were few and unpretentious; invariably arranged among themselves and for themselves. In a word, it was a little world of its own. Life there was easy, natural, and uneventful; such a charming simplicity was observed in everything that till my latest breath fondest memories will linger.”1

As for the homes in town Nicholls described them as :

"The little home was, generally, very neat and modest. The kitchen floor was bare but clean; its walls were whitewashed, its furniture largely home-made; the cook stove, black and shining. The ‘front room’ had a few cane-seated chairs, each with a little ‘tidy’ at the back, fastened with a pink ribbon. The only real luxury of any notable extravagance was a wood rocking chair with a cushion filled with chicken feathers. This chair was particularly reserved for company, and again during convalescence of any member of the family. It was generally understood that the rocking chair was not intended for daily use and that if any good wife was known to indulge in that luxury, it was regarded as an unquestionable sign of neglected household duties.” 2

But life was not easy on the mining frontier. Homes at Central had no insulation. They would be hot in the summer and so cold in the winter that, in some cases, sawdust was poured over bedroom windows and boarded up to prevent the blasts of winter from entering the room. All supplies had to be shipped by boat from ‘down below’ to the Keweenaw. Once Lake Superior iced over no more food or supplies could be expected until spring.

This 1910 photo shows one of the miner's homes in Central several years after the mine had closed. (KCHS)

This 1910 photo shows one of the miner's homes in Central several years after the mine had closed. (KCHS)

The winter of 1860 posed problems for those living at Central when on November 10, 1860, the wharf the company used at Eagle Harbor caught fire. Many of the supplies of food and material for the winter were destroyed. To compound the problem, the ship that was bringing the replacement supplies was caught in a storm and had to throw many of the replacement supplies overboard to avoid sinking. The only other way to get to Central other than boat was to take an over-night stage coach ride over the rugged road that ran down to Calumet, the nearest large town to Central.

The population of the town of Central varied as the mine would open, close, and then reopen depending upon the price the company received for the copper the miners raised from the ground. In 1882 over 1,200 people lived in 130 homes in Central. The school served 352 students. The town was served by both a Catholic and a Methodist Church. There were numerous lodges in town. The Central Mine F. & A. M., the Freemasons, Keweenaw Lodge No. 242 was organized in 1868 with 70 members, and in 1872 the Philanthropic Society of Sherman, a secret social society, formed a lodge in Central. The first Post Office in Central also opened that year. An 1873 R. L. Polk business directory showed several blacksmiths, builders, shoemakers, hotel and boarding house operators, a doctor, a lawyer, a justice of the peace, a general store, a meat market, and a tailor. The livery in town was large enough to shelter over 100 horses. In 1882, the ‘Good Templars’, I.O.G.T. Keweenaw Lodge 23 was chartered with 32 members at Central. The Lodge was remembered as “the main social affair” with dances as well as meetings taking place in its hall.

But the copper ran out as the mine went deeper. All work was suspended on August 1, 1894. Miners and their families began to leave Central for the Keweenaw mines still operating near Calumet and Houghton. The school closed as did the stores in town. Those who chose to stay at Central began to go to Eagle Harbor for goods and services. In 1905 the Central Mining Company was dissolved, and the Calumet and Hecla Mining Company purchased the property. The town slowly became a ghost town with many of the homes demolished and their wood used to build homes and camps in other locations. In 1907 the first of over 100 Central reunions was held. It is the spirit of these reunions that has kept the town of Central alive. Today the Keweenaw County Historical Society owns several of the remaining buildings at Central and operates them as a museum. The Methodist Church is now in the care of a Board of Directors that maintains the building and operates a Central Reunion the last Sunday in July of each year.

1- More Copper Country Tales, Volume II, Alfred Nicholls, 1968, Roy W. Drier publisher, page 33

2- More Copper Country Tales, Volume II, Alfred Nicholls, 1968, Roy W. Drier publisher, page 62

This document was written by L.J. Molloy for the KCHS.